2 Chronicles

Meditations on the Second Book of Chronicles, with a plan of Jerusalem

H. L. Rossier.

ISBN 0-88172-203-0

Believers Bookshelf Inc.

P. O. Box 261, Sunbury, Pennsylvania 17801

Contents

|

2 Chronicles 1-9 Solomon's Reign 2 Chronicles 1 A King According to God's Counsels 2 Chronicles 2 Solomon and Huram (Hiram) 2 Chronicles 3-5 The Temple. 2 Chronicles 6-7 Solomon's Prayer 2 Chronicles 8-9 Solomon's Relations With the Nations 2 Chronicles 10-36 2 Chronicles 14-16 … Asa 2 Chronicles 17-20 … Jehoshaphat |

2 Chronicles 20 War Again 2 Chronicles 21 Jehoram. 2 Chronicles 22 Ahaziah 2 Chronicles 23-24 … Joash 2 Chronicles 29-32 … Hezekiah 2 Chronicles 34-35 … Josiah |

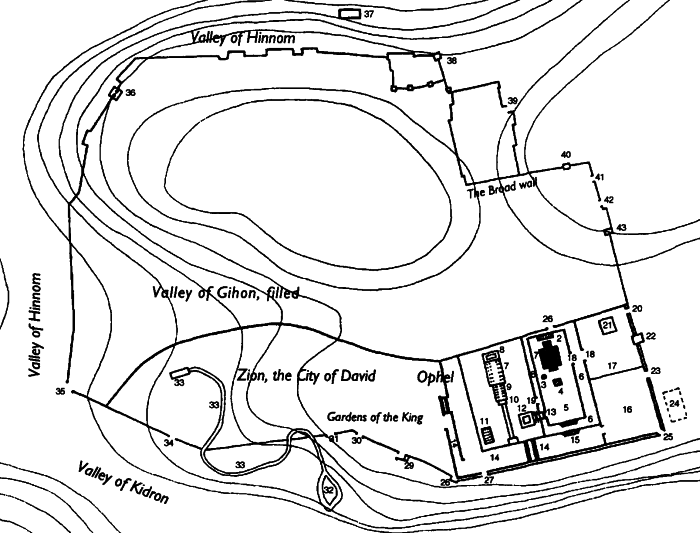

Legend

1 The Temple and the dwelling places of the priests.

2 Buildings of the Temple. Storehouse. 1 Chr. 26:15.

3 The Laver.

4 The Altar.

5 Temple court.

6-6-6 Outer court of the Temple.

7 House of the forest of Lebanon with pillars and side chambers* 1 Kings 7:2-5.

8 Porch of the throne. 1 Kings 7:7.

9 Porch of pillars. 1 Kings 7:6.

10 Flight of steps. 1 Kings 7:6.

11 House of Pharaoh's daughter. 1 Kings 7:8.

12 Solomon's House with inner court. 1 Kings 7:8.

13 Ascent to go up to the temple. 1 Kings 10:5.

14-14 Stairs and inclined slope from the City of David to the level of the temple.

15 Gate of Sur, or Gate of the foundation (Jesod), or the east Gate, or the King's Gate. 2 Kings 11:6; 2 Chr. 23:5; Neh. 3:29; 1 Chr. 9:18.

16 Perhaps a Reserve for the animals of the priests. See No. 23.

17 Residence of the “Couriers” or Temple guards.

18-18 Gate behind the Couriers. 2 Kings 11:16, 19. The North Gate. 1 Chr. 26:14, 17.

19 High Gate. 2 Chr. 23:20; 2 Chr. 27:3 or South Gate. 1 Chr. 26:17.

20 The Gate of Benjamin or the High Gate of Benjamin or the Prison Gate. Jer. 37:13; Zech. 14:10; Jer. 20:2; Neh. 12:39.

21 Prison (?)

22 Tower of Meah.

23 Sheep Gate. Neh. 3:1, 32; 12:39.

24 Pool of Bethesda.

25 Gate of Miphkad or the Ascent of the corner. Neh. 3:31.

26 The Gate Shallecheth or the West Gate. 1 Chr. 26:16.

27 Horse Gate. 2 Chr. 23:15; Neh. 3:28.

28 High Tower projecting from the King's house. Neh. 3:25.

29 Great projecting tower. Neh. 3:27.

30 Gate between two walls. 2 Kings 25:4; Jer. 39:4.

31 Water gate. Neh. 12:37.

32 The Overflowing Brook (or the brook which runs through the midst of the land), presently the Virgin's Fountain. 2 Chr. 32:4.

33-33-33 Hezekiah's aquaduct. 2 Kings 20:20 and the King's Pool. Neh. 2:14, or the Pool of Siloah. Neh. 3:15.

34 Fountain Gate. Neh. 2:14; Neh. 12:37.

35 Dung Gate. Neh. 2:13; Neh. 12:31.

36 Valley Gate and Tower of Uzziah. Neh. 2:13, 15; Neh. 3:13; 2 Chr. 26:9.

37 Pool of Gihon.

38 Pottery Gate and the Tower of the Furnaces. Jer. 19:2.

39 Gate of Ephraim. 2 Chr. 25:23. Cf. Neh. 8:16; Neh. 12:39.

40 Corner Gate and Tower of Uzziah. 2 Chr. 25:23; 2 Chr. 26:9; Jer. 31:38; Zech. 14:10.

41 The Old Gate or Gate of the Old Wall. Neh. 12:39.

42 Fish Gate. 2 Chr. 33:14; Neh. 3:3; Zeph. 1:10.

43 Tower of Hananeel. Neh. 3:1; Neh. 12:39; Jer. 31:38; Zech. 14:10.

Note: The location of numbers 7 and 13 on the site of Ophel is hypothetical.

Meditations on The Second Book of Chronicles

H. L. Rossier

Solomon's Reign

2 Chronicles 1-9

The second book of Chronicles continues on from the first book without transition; originally they formed a single account in the Hebrew manuscripts. We have previously remarked the same thing in the second book of Kings about these artificial divisions which are not part of the inspired Word. In fact, the account of the Chronicles is a continuous one until the end of Solomon's reign (2 Chr. 10), and if we are looking for a moral division in our subject, it will not properly be introduced until 2 Chr. 11.

Let us recall a truth, already mentioned many times in First Chronicles: in Chronicles God gives us, in the form of types, an overview of His counsels concerning Christ's royalty, counsels prefigured in the history of David and Solomon. Solomon himself symbolizes the future reign of wisdom and peace that will be inaugurated by the Lord's coming. This is why, as we have noted in 1 Chronicles in the history of David, Solomon's reign does not present any failures in Chronicles and even with the greatest carefulness, one cannot discover there the least allusion to the king's faults.

In the preceding book we have seen how Solomon was elevated to his father's throne before he was established on his own throne. These two facts speak very clearly to us of Christ's present heavenly kingdom and of His earthly kingdom which is yet to come. The account before us will present this latter to us, and here we will not find, as in Kings, a responsible and fallible sovereign, but rather the most perfect figure possible of a government of wisdom and of peace administered by the king according to the counsels of God.

2 Chronicles 1

A King According to God's Counsels

One cannot sufficiently emphasize, at the beginning of this book, that Solomon's reign in Chronicles has an entirely different character than that of Solomon in the book of Kings. His righteousness exercised in judgment on his father's enemies — Adonijah who had opposed David, Shimei who had insulted and mocked him, Joab whose acts of violence and unrighteousness he had tolerated without being able to rebuke them — all this is omitted in Chronicles (cf. 1 Kings 1-2). The incident of the two prostitutes (1 Kings 3:16-28) is also passed over in complete silence, for if this scene shows us Solomon's wisdom, it shows us his wisdom in the service of righteousness in order to rule equitably. The king does not pursue the investigation further, and does not rebuke or cut off even the most guilty of these prostitutes. Chronicles does not present Solomon's reign according to the character we have just mentioned. It is above all a reign of peace, presided over by wisdom. It is no less true that during the millennium “every morning [He] will destroy all the wicked of the land,” and that prostitution will be neither tolerated nor even mentioned; but peace will reign. It is this that constitutes the subject of the first chapters of this book.

From the very first words of our chapter (2 Chr. 1:1), Solomon is presented to us as strengthening himself in his kingdom, whereas in 1 Kings 2:46 the kingdom was established in his hand after the judgment of all the personal enemies of David. Solomon strengthens himself here with his full personal authority , but nonetheless he remains the dependent man, for if he were not, he would not be the type of the True King according to God's counsels. “Ask of me,” He is urged in Psalm 2, “and I will give Thee … for Thy possession the ends of the earth.” This is why in our passage we find: “And Jehovah his God was with him, and magnified him exceedingly.” So too, as long as He retains the kingdom, the Lord remains the dependent Man; when He shall have concluded its administration, He will faithfully give it up into the hands of the One who entrusted it to Him and “then the Son also Himself shall be placed in subjection to Him who put all things in subjection to Him” (1 Cor. 15:28). Will any earthly kingdom ever resemble this marvelous reign during which for a period of a thousand years — without a single shortcoming, without one denial of justice, without any decrease of peace — Christ will reign over His earthly people and over all the nations?

Dear Christian reader, let's get used to considering the Lord in this way for His own sake, and not only for the resources which He gives to meet our needs. This is the most lofty form of contemplation to which we are called, for we are set, so to say, in the company of our God to take delight in the perfections of this adorable Person. How numerous are those passages of Scripture that reveal, not what we possess in virtue of the work of Christ, but rather, what Christ is for God in virtue of His own perfections. God opens heaven on this Man and says: “This is My beloved Son, in whom I have found My delight.” And when He was obliged to close heaven to Him at the moment when He was making propitiation for our sins, He says: “But Thou art the Same, and Thy years shall have no end.” And again: “Thy throne, O God, is for ever and ever; a scepter of uprightness is the scepter of Thy kingdom: Thou hast loved righteousness, and hated wickedness; therefore God, Thy God, has anointed Thee with the oil of gladness above Thy companions.” In virtue of the perfection of His obedience and His humiliation, God “highly exalted Him, and granted Him a name, that which is above every name.” This Man is “the Firstborn of all creation”; He has all glory and all supremacy (Col. 1:15-20). It is because He laid down His life that He might take it again that the Father loves Him. In all this we find nothing of that which He has done for us. But in virtue of His accomplished work we are made capable of taking an interest in His Person and all His perfections. Let us cultivate this intimacy. Doubtless for our souls the outstanding trait of this adorable character is summed up in these words: “He loved me, and gave Himself for me”; whatever knowledge I may gain about Him, it always brings me back to His love. Thus, when He is presented to us as “the Prince of the kings of the earth,” we cry out: “To Him who loves us!” But what I want to say is that what He is in Himself is an unfailing source of joy for the believer. Nothing else so effectively takes him out of his natural egoism and out of the petty preoccupations of earth; he has found the source of his eternal bliss in a perfect Object, with whom he is in intimate and direct relationship.

In verses 2 to 6, we have the scene at Gibeon, but without the imperfections which spoil its beauty in 1 Kings 3:1-4. In our passage the “only” which denotes a fault has disappeared: “Only the people sacrificed in high places”; “Only he sacrificed and burned incense on the high places.” Here the scene is legitimate, if I may so express myself, and Gibeon is no longer “the great high place” (1 Kings 3:4); on the contrary, it is the place where “was God's tent of meeting which Moses the servant of Jehovah had made in the wilderness … and the brazen altar that Bezaleel the son of Uri, the son of Hur, had made, was there before the tabernacle of Jehovah” (2 Chr. 1:3-5). Not a shadow of anything that would discredit! Solomon sacrifices on the altar, the token of atonement, where the people could meet their God. Was there anything that could be reproached in that? Not at all. No, doubtless the place was only provisional while awaiting the construction of the temple; doubtless also, God's throne, the ark, was not to be found there, for from this time on it was established in the city of David; but in Chronicles Solomon comes to Gibeon with his people to inaugurate the reign of peace which God could introduce on the basis of sacrifice. Indeed, Second Chronicles, as we have already seen, speaks to us much more of the reign of peace than of the reign of righteousness.

In verses 7 to 12, Solomon asks God for wisdom, and here again our account differs significantly from that in Kings (1 Kings 3:5-15). In our passage, Solomon is not “a little child” who “know[s] not to go out and to come in.” There is no question that First Chronicles refers to him as a little child, but as we have noted in studying that book, from a typical point of view his youth corresponds to the position Christ occupies in heaven on His Father's throne before the inauguration of His earthly kingdom. In Kings, Solomon is ignorant and lacks discernment “between good and bad” (1 Kings 3:9). In Chronicles this flaw has totally disappeared: the king says that he needs wisdom to go out and come in before the people and to govern them. For this he addresses the One who has made him king and upon whom he is entirely dependent; this will also be Christ's relationship as Man and King with His God. But what is still more striking is that in our passage the question of responsibility is completely omitted, in contrast to 1 Kings 3:14: “If thou wilt walk in My ways, to keep My statutes and My commandments,” says God, “then I will prolong thy days.” In Chronicles, Solomon's responsibility is mentioned only once (1 Chr. 28:7-10), to depict Christ's dependence as Man, and not in any way to suppose that he might be found at fault. The book of Kings is completely different (see 1 Kings 3:14; 1 Kings 2:2, 6, 9; 1 Kings 6:11). Again, let us note that in 1 Kings God said to Solomon: “Because thou hast asked this thing … behold, I have given thee a wise and an understanding heart” (1 Kings 3:11-12). In 2 Chronicles God gives him wisdom and understanding “because this was in thy heart.” A type of Christ, he receives these things as man, but his heart did not need to be fashioned to receive them.

We shall not fail to see new proofs at every step of the marvelous precision with which the inspired Word pursues its object.

Verses 14-17. In the fact that Solomon accumulated much silver and gold at Jerusalem, and that his merchants brought him horses from Egypt, “and so they brought them by their means, for all the kings of the Hittites and for the kings of Syria,” some have thought to see proof of Solomon's unfaithfulness to the prescriptions of the law in Deuteronomy 17:16-17. The study of Chronicles causes us to reject such an interpretation. Here, Egypt is tributary to Solomon who treats it equitably. He lets foreign nations profit from the same advantages, and so it shall be under Christ's future reign. The same remark applies, as we shall see in 2 Chronicles 8:11, to Pharaoh's daughter.

2 Chronicles 2

Solomon and Huram (Hiram)

Here, as in all these chapters, we find King Solomon portrayed from the standpoint of the perfection of his reign. The nations are subject to him. The men to bear burdens, the stone cutters, and the overseers are taken exclusively from among the Canaanites living in the midst of Israel, whom the people had not succeeded in driving out (2 Chr. 2:1-2; 17-18; 2 Chr. 8:7-9): “But of the children of Israel, of them did Solomon make no bondmen for his work.” Thus a condition of things is realized under this glorious reign which, on account of the unfaithfulness of the people, had never existed previously. All their former mingling with the Canaanites has disappeared, and from now on the Lord's people are a free people that cannot be brought into servitude. Meanwhile the strangers whom unfaithful Israel had not exterminated from their land in time past are the only ones subjected to bondage, while the nations, possessing the riches of the earth and personified by the king of Tyre, are accepted as collaborators in this great work.

Here Solomon explains to Huram the meaning and significance of the construction of the temple, and he does so in a different way than in the book of Kings: “Behold, I build a house unto the name of Jehovah my God to dedicate it to Him, to burn before Him sweet incense, and for the continual arrangement of the showbread, and for the morning and evening burnt-offerings and on the sabbaths and on the new moons, and on the set feasts of Jehovah our God. This is an ordinance forever to Israel” (v. 4). Here the temple is the place where God is to be approached in worship, a place open not only to Israel, but also to the nations whom Huram represents. The temple is so much the place of worship in Solomon's mind, that only burnt offerings are mentioned here, without any reference to sin offerings; sweet incense of fragrant drugs, the symbol of praise, occupies the first place. When it is a question in Ezekiel 45 of the millennial service in the temple, whether for Israel, or for the “prince” of the house of David, Christ's viceroy on the earth, we find the sin offering, for all are in need of it. Here the thought is more general. Solomon declares to Huram that this great house which he is building is dedicated to the God of Israel “for great is our God above all gods. But who is able to build Him a house, seeing the heavens and the heaven of heavens cannot contain Him?” Thus, this sovereign God, this God who is supreme and omnipresent, cannot limit His kingdom to the people of Israel. As for Solomon himself, he knows that he is only a weak human likeness of the King according to God's counsels: “Who am I,” he says, “that I should build Him a house?” Nevertheless he is there “to burn sacrifice before Him.” He presents himself as king and priest, without any mediator; he himself offers pure incense, as the people's mediator, a select incense which rises with the smoke of the burnt offering, a perfect, well-pleasing odor to God, and “This is an ordinance forever to Israel.”

Solomon entrusts to Huram the direction of the work, while he himself is its executor, though confiding it into the hands of the nations. So it will be at the beginning of the millennium, according to what we are told about the temple in Zechariah 6:15 and about the walls of Jerusalem in Isaiah 60:10.

The sustenance of Huram's workers here depends entirely on the king: He is the one who offers and appoints it (v. 10), and Huram has nothing more to do than to receive it. It is otherwise in 1 Kings 5:9-11 where Huram requests it and Solomon grants it.

Huram (v. 11) acknowledges in writing (That which is written is an abiding declaration and is always available for reference): “Jehovah loved His people” in establishing Solomon as king over them, and he blesses “Jehovah the God of Israel,” but as Creator of the heavens and the earth — lovely picture of the praise of the nations who, in the age yet to come will submit themselves to the universal dominion of the Most High, Possessor of the heavens and the earth, represented by the true Son of David in the midst of His people Israel. Thus blessing will rise up to God Himself from those who, formerly idolaters, will be subjected to the dominion of Christ, the King of the nations.

Huram is prompt to execute all that the king requires, and is prompt also to accept Solomon's gifts. In Chronicles we do not see him disdainfully calling the cities which Solomon gives him “Cabul” (cf. 1 Kings 9:13), and in this way the fault committed by Solomon in alienating the Lord's inheritance is passed over in silence. Here on part of the representative of the nations there is only thankfulness and voluntary submission; he is prompt to accept and to receive, for to refuse the gifts of such a king would be only pride and rebellion.

2 Chronicles 3 - 5

The Temple

2 Chronicles 3 and 2 Chronicles 4 correspond to 1 Kings 6 and 1 Kings 7, but with the difference that here the temple has a special significance. Whereas in Kings it is on the one hand the place where God dwells with His own, and on the other hand the center of His government in the midst of Israel, in Chronicles, as we have already noted, it is the place where one approaches God in order to worship Him, the “house of sacrifice” (2 Chr. 7:12). In speaking of a place of approach we are not alluding to the sinner who comes by the blood of Christ to be justified before God; we are thinking of the worshipper who enters by that same way into the sanctuary. Thus in the Epistle to the Romans we see the sinner justified by Christ's blood, whereas the Epistle to the Hebrews introduces us into the most holy place by that same way. The fact that the temple is presented as the place of approach explains all the details of this chapter. Here we again find the brazen altar and the veil (2 Chr. 3:14; 2 Chr. 4:1), omitted in the description of the temple in the book of Kings; on the other hand, the priests' dwellings mentioned in Kings are missing in Chronicles. The prophet Ezekiel, who does not give us the typical picture but rather the actual description of Christ's millennial reign, in his description of the temple (Ezek. 40-45) brings together the characters of the books of Kings and Chronicles. There we find the altar, the door of the sanctuary, the dwelling places of the priests, and the attributes of God's government all together (Ezek. 40:47; Ezek. 41:22; Ezek. 41:6; Ezek. 41:18). In fact, Ezekiel's temple sets forth Jehovah, Christ, dwelling in the midst of a people of priests, exercising His righteous government, and become the center of worship for both Israel and the nations; whereas the books of Kings and Chronicles, in order that we may better appreciate His glories, present them to us one after the other.

Other striking details confirm what we have just said. Chronicles mentions neither the sin offering nor the trespass offering; there the altar is solely the place of burnt offerings and peace offerings. Ezekiel, by contrast, insists upon the sin offering as the preparation for all the other offerings (Ezek. 43:25-27), and then names them not omitting even one (Ezek. 45:25).

A few more words about the brazen altar: This altar of Solomon's has a very important place in Chronicles. It is not the altar of the wilderness, kept at Gibeon, figure of the way in which God comes to meet the sinner and remains just while justifying him; but rather, it is the altar of burnt offering without which one may not approach Him. The dimensions of the altar at Gibeon are quite different from those of Solomon's altar: the first is five cubits long, five cubits wide, and three cubits high. Solomon's altar (2 Chr. 4:1) is twenty cubits long, twenty cubits wide, and ten cubits high. The two principal dimensions are exactly the same as those of the most holy place (2 Chr. 3:8; 1 Kings 6:20; Ezek. 41:4). The altar, Christ, is perfectly suited to the sanctuary; the glories of the most holy place correspond to the greatness and perfection of the sacrifice represented by the altar. Moreover, as we have said, the altar being especially the expression of worship here, it also has the same measurements as the sanctuary; without being perfect in all its dimensions, it is worthy, in the highest degree, of the millennial scene which it represents.

Everything pertaining to Christ's millennial government and even to the emblems of this government is completely absent in Chronicles; for example, the house of the forest of Lebanon, seat of the throne of judgment, as well as the king's palace, and also the cherubim, special symbols of government which are found throughout the book of Kings, on the walls of the temple and even on the vessels of the courtyard.

Even when it is a question of Solomon's person and his deeds, the description which Chronicles gives is intentionally simplified. There the king is presented to us, not increasing in greatness, as in the book of Kings, but established on the throne according to God's counsels, endowed with perfect wisdom, surrounded by riches and glory. Not a single detail is given us about the exercise of his wisdom, whether in discerning evil, whether in judging, or whether in teaching that which is good by his words and writings (see 1 Kings 3:16-28; 1 Kings 4:29-34). Solomon is set before our eyes on his throne, in a posture, so to say, unchangeable; peace reigns, the counsels of God concerning His King are fulfilled, and this King Himself is God.

This scene of peace and well-being has its starting point on Mount Moriah, a detail, let us carefully note, which is missing in the book of Kings: “And Solomon began to build the house of Jehovah at Jerusalem on mount Moriah, where he appeared to David his father, in the place that David had prepared in the threshing floor of Ornan the Jebusite” (2 Chr. 3:1). It was at Moriah, first of all, that Abraham had offered Isaac on the altar and received him again in figure by resurrection; there, all that the holiness of God demanded had been provided. Next, it was at Moriah where, on the occasion of David's failure, grace gloried over judgment. Solomon's reign of peace is thus established after resurrection, on the principle of grace, just as the future reign of the risen Christ will be based entirely on the grace that triumphed at the cross. Following the sacrifice of Moriah and in virtue of the sovereign monarch's personal perfection, the latter may from this time forward enter his temple. The eternal gates will lift up their heads to let the King of glory pass. He will have a rich entry into His own kingdom. Only in Chronicles do we find the immense height of this porch (2 Chr. 3:4; cf. Ps. 24:7, 9; Mal. 3:1; Hag. 2:7; 2 Peter 1:11, 17).

One more characteristic detail: here we see only palm trees and chains on the walls of the house; palm trees are the symbols of triumphant peace; the chains, which also ornament the pillars here, are not mentioned anywhere else except on the shoulder pieces and the breastplate of the high priest. They firmly unite the various parts and appear to symbolize the solidity of the bond uniting the people of God. There are no more partially opened flowers, symbol of a reign that is beginning to blossom out, as in the book of Kings; here the reign is definitely established; there are no more cherubim hidden under the gold of the walls; they appear only on the veil; there are no more secret thoughts, no more hidden counsels of God; they are now made manifest in the person of Christ, but fixed on the veil — His flesh delivered to death. In the most holy place, two cherubim standing with wings extended face “toward the house” (2 Chr. 3:13), a fact mentioned only here, and contemplate the order of the people of God established from henceforth on. The pillars Jachin and Boaz (“He shall establish” and “In Him is strength”) are essential to this scene, emblems of a reign established from this time on and dependent entirely on the power which is in Christ.

Another interesting detail: Solomon “made ten tables, and placed them in the temple, five on the right hand and five on the left” (2 Chr. 4:8). 1 Kings 7:48 mentions only one. Is it not striking to see the loaves of shewbread thus multiplied tenfold? Solomon is viewed as seated “on the throne of Jehovah” (1 Chr. 29:23); Israel increases under his reign; they ever remain the same tribes, but infinitely increased in the eyes of God, who beholds them and governs them. The true Solomon, Christ Himself, is the author of this multiplication (2 Chr. 4:8). In the millennium Israel will be complete, as presented to God by Christ, an offering well-pleasing to God.

In 2 Chronicles 5 the ark is brought up from the city of David to the magnificent house which Solomon has prepared for it. The tabernacle and all its vessels, which were at Gibeon, rejoin the ark in the temple: thus the remembrance of the wilderness journey ever remains before God. We are not told of the vessels of the court; most importantly, we are not told of the brazen altar that was set up by Moses and where God in grace came to meet a sinful people. This wilderness altar is replaced by Solomon's altar, itself corresponding to the altar David set up on the threshing-floor of Ornan. Solomon's altar is mentioned in passing in the book of Kings only when all has been finished (1 Kings 8:22). Kings, as we have said, has another object in view than worship. The ark has at last found a place of rest, but the millennial scene, which these chapters pre-figure, is not the eternal, final rest for God's throne. The staves have not disappeared, although their position denotes that the ark will no longer journey. The entire scene of millennial blessing described here will end when the new heavens and the new earth are established.

The passage from verse 11 to 14 of our chapter is missing in the book of Kings: “And it came to pass when the priests were come out of the holy place (for all the priests that were present were hallowed without observing the courses; and the Levites the singers, all they of Asaph, of Heman, of Jeduthun, with their sons and their brethren, clad in byssus, with cymbals and lutes and harps, stood at the east end of the altar, and with them a hundred and twenty priests sounding with trumpets), — it came to pass when the trumpeters and singers were as one, to make one voice to be heard in praising and thanking Jehovah; and when they lifted up their voice with trumpets, and cymbals, and instruments of music, and praised Jehovah: For He is good, for His loving-kindness endures forever; that then the house, the house of Jehovah, was filled with a cloud, and the priests could not stand to do their service because of the cloud; for the glory of Jehovah had filled the house of God.” This is the appropriate picture of millennial worship when the “song of triumph and praise” shall be sounded (cf. 2 Chr. 20:22). There the Lord is praised “for He is good, for His loving-kindness endures forever.” (As to this song, see also: 1 Chr. 16:41; 2 Chr. 7:3, 6; Ps. 106:1; Ps. 107:1; Ps. 118; Ps. 136; Jer. 33:11). All the instruments of music resound, just as in Psalm 150 which describes the same scene. Here we have properly the dedication of the altar (2 Chr. 7:9) preceding the feast of tabernacles, but only Chronicles shows us the glory of the Lord filling the house twice. In fact, there were two feasts, one of seven days, the dedication of the altar, and one of eight days, the dedication of the house or the feast of tabernacles (2 Chr. 7:9). Both are found here, with the same hymn and the same presence of God's glory in His temple, a subject most appropriate to this book which speaks of worship and of the fulfillment of God's counsels concerning His reign.

In Chronicles the dedication of the altar takes the place of the great day of atonement (cf. Lev. 23:26-36), while in Zechariah this day must precede the establishment of the messianic reign. Here it is not a question of afflicting their souls as on the day of atonement (Lev. 16:29), but of rejoicing, for by means of the altar God's loving-kindness which endures forever has ultimately brought the people to Himself.

The song: “His loving-kindness endures forever,” so characteristic of the beginning of the millennial reign, is repeated in this book of Chronicles both times when the glory of Jehovah fills the temple; this hymn is completely absent in 1 Kings. The scene is much more complete here: the counsels of God as to the establishment of Christ's kingdom on earth are in type at last accomplished. “The glory of Jehovah had filled the house of God” (cf. 1 Kings 8:11). The name of God often replaces that of Jehovah in these chapters, an allusion to His relationship with the nations which acknowledge the God of Israel as their God.

In conclusion let us say that in the presence of all the differences in details between 1 Kings and 2 Chronicles, every believer will be convinced of the wisdom and divine order which invariably preside in these accounts. The smallest omission as well as every word added in the sacred text are the fruit of an overall plan destined to display the various glories of Christ. We are far from having exhausted the enumeration of these differences; others may discover additional differences with real profit for their souls.

2 Chronicles 6-7

Solomon's Prayer

Many important particulars differentiate this portion of our book from the corresponding chapter of Kings — 1 Kings 8. In the latter chapter, the feast, although prolonged for fourteen days, in actual fact corresponds only to the feast of tabernacles. It is called “the dedication of the house” (cf. 1 Kings 8:63); but on the eighth day, the great day of the feast, the king sent the people away (1 Kings 8:65-66). The passage in Chronicles goes much further: it insists on the fact that “on the eighth day they held a solemn assembly” (2 Chr. 7:9); thus it introduces the type of ultimate general rest connected with the day of resurrection which the eighth day prefigures. In this way, the blessing is not restricted to the people of Israel alone, but belongs to all who have part in the day of resurrection.

Our passage in Chronicles offers another very interesting observation: Solomon stood before the altar of the Lord, in the presence of the whole congregation of Israel, “and spread forth his hands. For Solomon had made a platform of bronze, five cubits long, and five cubits broad, and three cubits high, and had set it in the midst of the court; and upon it he stood, and he kneeled down on his knees before the whole congregation of Israel” and spread forth his hands towards the heavens. The entire portion of this passage within the quotation marks is lacking in the book of Kings. The platform Solomon made and on which he stood in the presence of all the people had exactly the same dimensions as the brazen altar in Exodus 27:1. “And thou shalt make,” the Lord had said to Moses, “the altar of acacia wood, five cubits the length, and five cubits the breadth; the altar shall be square; and the height thereof three cubits.”

The wilderness altar was, as we have already said, one of the vessels not mentioned as having been brought from Gibeon to the temple (2 Chr. 5:5 & 1 Kings 8:4), for a new altar had been constructed there. But could the first altar be absolutely excluded? That was impossible! The altar of Moses represented solely the place where God could meet the sinner. A type of the cross, it was there that God could manifest Himself as righteous in justifying the guilty, and it was there that His love was in perfect accord with His righteousness to accomplish salvation. The brazen altar formed the basis of all of the Lord's relationships with his people; it was, so to speak, the first door of access to the sanctuary. Nevertheless our book passes over it in silence (not over its memorial, as we shall see) for the work introducing the reign of the King of peace is considered here as completely finished. The altar of the tabernacle, the altar of atonement, in Chronicles is merely the starting point for leading the people to the altar of the temple, that is to say, to the altar of worship, the essential characteristic of Solomon's altar in this book. Thus the first altar of bronze has disappeared, only to reappear here in form of a platform, as a pedestal on which Solomon is placed in the sight of all the people. The place where the sin offering was sacrificed becomes the place where Solomon — Christ — is glorified. “Now,” says the Lord, speaking of the cross, “is the Son of man glorified, and God is glorified in Him” (John 13:31). This altar, representing final salvation forever for every believer — for for us there is no more sin offering: the cross of Christ henceforth remains void of its burden of iniquity — this altar has yet another meaning: it is the basis upon which the Son of man's glory is established. Because of His sacrifice the reins of government are placed in His hands, and He is presented as the Leader of His people.

But something else strikes us here: Solomon on his platform in reality is much more an intercessor, an advocate for Israel, than a king. There, on the platform he bows the knee and spreads forth his hands in supplication toward heaven. And remarkably, here he is not, as in 1 Kings 8:54-61, a high priest according to the order of Melchizedek, blessing God on behalf of the people and blessing the people on behalf of God, rising from before the altar to stand and bless: no, on his platform which once was an altar he assumes only the place of an intercessor, praying for the people who through their future conduct, their sin already to be seen, would bring to naught all God's counsels, if indeed His counsels could be brought to naught.

This role that Solomon filled on behalf of Israel is the very role the Lord fills today on our behalf. “If any one sin, we have a patron with the Father, Jesus Christ the righteous; and He is the propitiation for our sins; and not for ours alone, but also for the whole world” (1 John 2:1-2). His office as Advocate is based on the propitiation which He has accomplished, just as Solomon's intercession was inseparable from this platform, mysterious and marvelous figure of the altar.

At the end of Solomon's prayer we find (2 Chr. 6:41-42) these words which are absent in the book of Kings: “And now, arise, Jehovah Elohim, into Thy resting-place, Thou, and the ark of Thy strength: let Thy priests, Jehovah Elohim, be clothed with salvation, and let Thy saints rejoice in Thy goodness. Jehovah Elohim, turn not away the face of Thine Anointed: remember mercies to David Thy servant.” These words are taken from Psalm 132. In this song, the object of David's afflictions was to find a habitation for the Mighty One of Jacob. This habitation had now been found, but in the imperfection which Solomon's request reveals. God in that Psalm then responds to the king's desire expressed in Chronicles. He shows him Zion, His house, His priesthood, His Anointed, as He sees them in their eternal perfection in answer to sufferings of Christ, the true David. God's rest is still to come, but here Solomon shows us that scene we anticipate.

Next in 2 Chronicles 7 we find in verses 1-3 and 6-7 a passage which is lacking in the book of Kings. “The fire came down from the heavens and consumed the burnt offering and the sacrifices; and the glory of Jehovah filled the house.” God sets His seal and His approval on the inauguration of this reign of peace; His glory fills the house which has been prepared for Him; all the people bow themselves with their faces to the ground, and extol the Lord with worship and praise. This passage tallies with and admirably harmonizes with the character of the millennial worship, as presented in Chronicles!

Verses 12 to 22 of 2 Chronicles 7 differ little from the account of Kings. Nevertheless it should be noted that here, as in 2 Chronicles 1:7, the Lord's appearance to Solomon has a character perhaps more direct than in the book of Kings, for it is not said that God appeared to him “in a dream” (v. 12). The house which the Lord had chosen is called “a house of sacrifice” according to its character as a place of worship which we have observed all through this book. God's free choice in grace is also emphasized more in our chapters: God chose Jerusalem, chose David, chose the house (2 Chr. 6:6; 2 Chr. 7:12). In response to the office of advocate and intercessor which Solomon had taken in the preceding chapter, God gives him a full answer (vv. 13-14) which is absent in Kings. The consequences of the responsibility of the people and their leaders are exposed completely in this passage, as they had been in Solomon's prayer, but also the certainty that, by virtue of this intercession, God would forgive their sin and heal their land. And He assures His Beloved by this single word, omitted in the book of Kings: “Now mine eyes shall be open,” etc. From the moment Solomon appears before God, the answer to his intercession is sure and, however delayed it must be on account of the people's unfaithfulness, it is no less real a fact granted at the request of the Lord's anointed.

For the second time in these books, Solomon's responsibility is mentioned (vv. 17-18. See 1 Chr. 28:7); but with the great difference that Chronicles in no way shows, as does the first book of Kings, that Solomon failed therein. Thus in our book his responsibility remains a responsibility to the glory of God, so that in type we see absolutely nothing lacking in the king of the counsels of God.

2 Chronicles 8 - 9

Solomon's Relations With the Nations

These two chapters describe King Solomon's relations with the Gentiles. 2 Chronicles 2 has already referred to the Canaanites and to Huram, king of Tyre, but only in relation to the construction of the temple, the work to which all were called to contribute. The first event related is the peaceful conquest, taking possession of and subjugating all the cities of the surrounding nations. Here we find a detail which is very interesting for understanding Chronicles. The first book of Kings (1 Kings 9:11-14) tells us that Solomon gave Hiram, the king of Tyre, “twenty cities in the land of Galilee.” Hiram despised this gift and called these cities the “land of Cabul” (good for nothing); and we have noted that if, on the one hand, the territory of the promised land never had any value for the world, on the other hand Solomon committed positive unfaithfulness in alienating Jehovah's land. As always in this book, Solomon's sin is passed over in silence. Such omissions, repeated over and over again, ought to show rationalists the futility of their criticisms in presence of a design of which they seem unconscious. Instead of seeing Solomon giving cities to Huram, in verse 2 we see the latter giving cities to Solomon. A day is coming when the world, which Tyre represents in the Word, will come with its riches and acknowledge itself tributary to Christ, and offer its finest cities as dwelling places for the children of Israel. Solomon fortifies them, surrounds them with walls, equips them with gates and bars — in a word, prepares them for defense. There, too, he concentrates his armed forces, not to use them for warfare, but, knowing the unsubmissive heart of the nations, he prepares this power so that peace can rule. During his long reign of forty years we never see Solomon engaged in any war of conquest, but the weight of his scepter must be felt so that the nations will submit. The Word tells us, speaking of Christ: “Thou shalt break them with a scepter of iron.” During the millennium no nation will dare to lift the head in presence of the King, and He will have many other means, too, of making them feel the weight of His arm (see Zech. 14:12-16).

All the Canaanites remaining in the land of Israel also are subjected to Solomon (vv. 7-10), whereas the children of Israel are men of war and free, but free to serve the King.

Verse 11 tells us of Solomon's relations with Pharaoh's daughter: “And Solomon brought up the daughter of Pharaoh out of the city of David to the house which he had built for her; for he said, My wife shall not dwell in the house of David king of Israel, because the places are holy to which the ark of Jehovah has come.” Many have thought that Solomon's union with the daughter of the king of Egypt was an act of unfaithfulness to the prescriptions of the law. Forgetfulness of the typical meaning of the Word may lead to such mistakes. Would we say that Joseph was unfaithful in marrying Asenath, the daughter of Potipherah, priest of On (Gen. 41:50)? that Moses was unfaithful in marrying Zipporah, daughter of the priest of Midian (Ex. 2:21)?

Always in their relations with the Canaanites, even long before Israel's entrance into the Promised Land, the Pharaohs had given their daughters to various kings of these countries. For the king of Egypt it was a means of subjecting them, for they paid tribute to Pharaoh in exchange for the honor of being his sons-in-law. But never did the king of Egypt give his own daughter to the kings of the neighboring nations; to them he granted his concubines' daughters who had no right to the throne of Egypt and who were not of royal blood through their mothers. “The daughter of Pharaoh” was the daughter of the queen, his legitimate wife, and according to the Egyptian constitution she had the right to the throne in the absence of a son and heir. This daughter, the daughter of Pharaoh — not “one of his daughters” — was given to Solomon. Such a union was the affirmation of Solomon's eventual rights to the land of Egypt. It subjected Pharaoh's royalty to that of Israel's king who could thus become the ruler to whom Egypt must submit; evident proof that the most ancient of earth's kingdoms was consenting to submit to the yoke of Israel's great king. This fact has very real importance as one of the features of Christ's millennial dominion. A word added here is not found in the book of Kings: Solomon said, “My wife shall not dwell in the house of David king of Israel, because the places are holy to which the ark of Jehovah has come.” A daughter of the nations, however ancient and powerful her people might be, could not live there where the ark had even momentarily dwelt. Despite the union of the King of Peace with the nations, they could not enjoy the same intimacy with him as the chosen people. The ark was Jehovah's throne in relation to Israel; God had never chosen Egypt, but He had chosen Israel as His inheritance, Jerusalem as His seat, the temple as His dwelling place, and David and Solomon to be the shepherds of His people.

This people, today despised and rejected on account of their disobedience, will one day on account of the election by grace again find earthly blessing in Christ's kingdom, and in the Lord's presence. The great nations of the past, Egypt and Assyria, will receive a generous portion, but not that of absolute nearness (Isa. 19:23-25); they will be called the Lord's people and the work of the Lord's hands, but not His inheritance, as is Israel. Doubtless the fierce oppressors of God's people in former days will have a place of privilege and blessing during Christ's reign, but it will be becoming to the glory of the King, once scorned and set at naught by the nations who oppressed His people, that His people receive highest honors in the presence of their former enemies. And will it not be the same for the faithful Church, when those of the synagogue of Satan will come to bow down at her feet and acknowledge that Jesus has loved her?

Verses 12-16 mention all the religious and priestly service as set before the eyes of the subjected nations and as having great importance for them. Everything is regulated according to the commandment of Moses and the ordinance of David. Sacrifices are offered (“as the duty of every day required”), but only the burnt offerings are mentioned. This is in accord with the design of the book, as we have already said more than once. This passage (vv. 13-16) is absent in the first book of Kings.

In verses 17-18 we once again find the king of Tyre's contribution to the splendor of Solomon's reign. It is no longer just a matter of his collaboration in the work of the temple, but one of contributing to the outward opulence of this glorious reign under which gold was esteemed as stones in Jerusalem.

In 2 Chr. 9 the history of the queen of Sheba, so full of instruction and already dealt with in meditations on the book of Kings, closes the account of Solomon's intimate relations with the nations. We will limit ourselves to a few additional remarks.

Huram placed himself at Solomon's disposal out of affection for David, the king of grace, whom he had personally known; the Queen of Sheba is attracted by the wisdom and fame of the King, whose glorious and peaceful reign is the object of universal admiration. The word of others convinces her to come and see with her own eyes. She “heard of the fame of Solomon.” 1 Kings 10:1 adds: “in connection with the name of Jehovah”; but here Solomon, seated “on the throne of Jehovah” (1 Chr. 29:23), concentrates, so to say, the divine character in his person. We find the same thing in verse 8: “Blessed be Jehovah thy God, who delighted in thee, to set thee on His throne, to be king to Jehovah thy God!” whereas 1 Kings 10:9, the corresponding passage, simply says, “to set thee on the throne of Israel.” Thus it is Jehovah whom Solomon represents in Chronicles. One could multiply such details to show that they all work together, harmonizing in the smallest shades of difference in the picture given us here of Christ's millennial reign.

The Queen of Sheba needed nothing beyond what she had heard to make her hasten to Jerusalem; nevertheless she “gave no credit to their words” until she had come and her eyes had seen (2 Chr. 9:6). This will indeed be characteristic of believers in the days yet to come; their faith will spring from sight, whereas today, “Blessed they who have not seen and have believed” (John 20:29).

If the queen's joy was deep in presence of the splendors of this great reign, can her joy be compared to ours in the present day? Is it not said of us: “Whom, having not seen, ye love; on whom though not now looking, but believing, ye exult with joy unspeakable and filled with the glory” (1 Peter 1:8)?

All the details of this incomparable reign are of interest to the Queen of Sheba; she rejoices in all, sees all, enumerates all — from the apparel of his servants to the marvelous ramp built by Solomon to connect his palace with the temple. Every treasure flows to Jerusalem, the center to which the king was drawing the riches of the entire world. “All the kings of Arabia” and the governors of various districts bring him gold, spices (which played such a considerable role in oriental courts), precious stones, and rare sandalwood. Gold in particular, that emblem of divine righteousness, came from all parts; the very footstool of the throne was made of gold (2 Chr. 9:18). The king's feet rested on pure gold when he sat on the throne of his kingdom. “Righteousness and judgment are the foundation of thy throne,” Psalm 89:14 tells us (cf. Ps. 97:2); but it also adds: “loving-kindness and truth go before thy face.” It was his presence which all the kings of the earth sought after, to hear his wisdom, which God had put in his heart (v. 23). “To behold the face of the king” was the supreme privilege; whoever was admitted to his presence could count himself happy. “Happy … thy servants,” said the queen, “who stand continually before thee.” “Blessed,” it says again, “is the people that know the shout of joy: they walk, O Jehovah in the light of Thy countenance” (Ps. 89:15). To see the king's face is to be admitted to his intimacy. Supreme honor for the nations of the future, but so much the more our present day privilege! Ah, how such favor humbles us! We feel our nothingness before this glorious presence; we bow in the dust before such righteousness, wisdom and goodness. But here is what is said to us: “Happy”, says the queen, “are these thy servants, who … hear thy wisdom.” It is not the voice of great waters and loud thunder, but a voice more gentle than the myrrh-scented breeze; a voice that goes through us; the voice of the Beloved, of Jedidiah, the voice of love! All these sentiments come from seeking His face and being admitted to His presence. And as happened with the queen of Sheba, there will be no more spirit in us. There is wonder and worship in the presence of such wisdom, holiness, righteousness, and glory; a very humble love, for it immediately senses that it is not to be compared with this love; the whole heart is ecstatic and longs only to lose itself in the contemplation of its cherished object. Such were the thoughts of the Shulamite when she contemplated the most perfect of the sons of men. Her eyes saw the King in his beauty (Isa. 33:17).

Verses 27-28, repeating what was told us in 2 Chronicles 1:15, 17 (cf. 1 Kings 10:27-29), describe the reign as it was established from its beginning and as in Chronicles it remains until the end. According to the character of this book, it has come up to all that God was expecting of it. One sees from verse 26 that Solomon's chariots and horses were not an infraction of the law of Moses (Deut. 17:16), but a means of maintaining his reign of peace over all the nations: “He ruled over all the kings from the river as far as the land of the Philistines, and up to the border of Egypt” (2 Chr. 9:26). These limits of the kingdom of Solomon in Israel correspond to those which God's counsels had assigned to His people in Joshua 1:4; they had never before been attained nor have they ever been since. They will only be realized, and that in even greater measure, in the future reign of Christ.

Thus in these chapters we have seen the Canaanites, Tyre, the kings of Arabia, all the kings from the River to the border of Egypt, the Queen of Sheba, and lastly, all the kings of the earth converging upon the court of the great king. Thus ends the history of Solomon, without any alloy whatsoever tarnishing the pure metal of his character as Chronicles presents it. If we have alluded to his love, let us recall however that this is here not so much the hallmark of his reign as are wisdom and peace, but that Jehovah is celebrated on account of His loving-kindness which endures forever. Even his righteousness is presented in Chronicles only in the government of the nations; his throne is described (2 Chr. 9:17-19) because it has to do with the kingdom, but the house of the forest of Lebanon where the throne is found in its judicial character, is completely absent here (cf. 1 Kings 7:2-7). In that which is presented to us everything is perfect, and it is astonishing that writings of pious people can affirm the very opposite. No doubt this is because these persons confuse the books of Kings and Chronicles. As a type, the Word can go no further, but let us remember that it cannot give us a picture of perfection when it uses the first Adam as an example unless it passes over his imperfections and serious sins in absolute silence.

At this point in our account we must notice the absolute omission in Chronicles of 1 Kings 11:1-40: Solomon's sin which was not forgiven; his love for many foreign women; the idolatry of his old age; God's wrath aroused against him; the adversaries raised up against him, Hadad the Edomite, and Rezon the son of Eliada (1 Kings 11:14-25); the judgment pronounced on his kingdom (1 Kings 11:11); and lastly, Jeroboam's revolt. Now such omissions make the purpose and general thought of our book shine out before our eyes.

Solomon's Successors

The Era of the Prophets

2 Chronicles 10-36

2 Chronicles 10 marks the second division of Chronicles. Its first division has embraced the history of David and Solomon. Until the end of our book we now have the history of the kingdom of Judah, the counterpart of the kingdom of Israel taken up in the books of the Kings. But before studying Solomon's successors, we must give a brief exposition of what makes their history special.

We have said that Chronicles presents the picture of God's counsels with regard to the kingdom. These counsels have been accomplished in type, but only in type, under the reigns of David and Solomon. David, the suffering and rejected king, has become, in his Son, the king of peace, the king of glory who sits upon the throne of Jehovah. However, although Chronicles is careful to omit Solomon's faults entirely, he was not the true king according to God's counsels. The words “I will be his father, and he shall be My son” (2 Sam. 7:14) could not find their complete fulfillment in him. The decree “Thou art My Son; I this day have begotten thee” (Ps. 2:7), did not relate to him, but directed hope to One greater and more perfect than he. But, in order that this future Son might be “the offspring of David,” David's line must be maintained until His appearing; this is why God had promised David “to give to him always a lamp, and to his sons” (2 Chr. 21:7). Now, how was this lamp going to shine in the royal house until the appearing of the promised Son? How was it to pass through man's poisoned air and moral darkness without being extinguished — which would have made David's true Heir's appearing impossible? Satan understood this. If he could succeed in extinguishing the lamp, all of God's counsels concerning the “Just Ruler over men” would come to naught. But, despite all the enemy's efforts to suppress this light, the Son of David appeared in the world, won the victory over Satan, and became for the Church the Yea and Amen of all God's promises. Yet this subject, revealed in the New Testament, is not what is in question here; as we have seen, Chronicles deals only with the earthly kingdom of Christ over Israel and the nations. This kingdom was contested to the end by Satan. When the King whom the magi worshipped appeared as a small Child, the enemy sought to cut Him off through the murder of the children at Bethlehem. At the cross where he thought to make an end of Him, he could not prevent Him from being declared king of the Jews in sight of all by Pilate's inscription; and, when the enemy thought he was victorious, God resurrected His Anointed and made Him Lord and Christ before the eyes of the whole house of Israel.

Let us return to our book. If for the reasons above it does not show us Satan's maneuvers during Solomon's reign, it speaks of them in an all the more striking manner during the subsequent reigns. The enemy seduces the king and his people to lead them into idolatry; he uses violence in an effort to destroy and wipe out the royal line. But God's watchful care reaches the people's conscience and, when everything seems lost, the Spirit's breath comes to revive the wick that is going out. There are situations where a Joram, an Ahaziah, an Ahaz are so reprobate that they are delivered up to consuming fire, for God Himself, always mindful of “good things,” can no longer acknowledge any good in these kings, and everything, absolutely everything, must be judged. The lamp is extinguished; deepest darkness reigns; Satan triumphs, but only in appearance. God preserves a feeble shoot of this reprobate trunk in the person of Ahaziah — yes, but this single shoot spared from the murder of the royal race, is himself found to be a dry branch destined for the fire. Anew the entire line is annihilated. Is it completely destroyed now? No, there it is — reborn in the person of Joash, and the Spirit of God is once again able to find in him “good things.” In this manner the royal succession continues, so that David's line is not wiped out by these reprobates (see Matt. 1). Thus Satan's struggle against God results in Satan's confusion. What, then, is the reason for his defeat? One thing explains it: the only thing that Satan, who knows so much, has never thought of nor could think of. The secret which he is ignorant of is grace, for his so cunning intelligence is completely impervious to love. This entire second portion of Chronicles could thus be entitled The history of grace in relation to the kingdom of Judah. When grace can revive the flame so as to maintain the light of testimony, it does not fail to do so; when, in the face of the willful hardening of heart of the kings, it can produce nothing, it still raises up to them a posterity from which it can expect some fruit.

Thus we shall witness Satan's desperate struggle against God's counsels and, at the same time, the triumph of grace. This entire period is summarized in the words of the prophet: “Who is a God like unto Thee, that forgives iniquity, and passes by the transgression of the remnant of His heritage? He retains not His anger for ever, because He delights in loving-kindness. He will yet again have compassion on us; He will tread under foot our iniquities: and Thou wilt cast all their sins into the depths of the sea” (Micah 7:18-19).

Nevertheless a time comes when the ruin appears irremediable, when in the struggle Satan's triumph seems assured. The kingdom sinks under waves of judgment; although, as we have seen in the genealogies (1 Chr. 3:19, 24), feeble representatives of the royal line, without titles, without prerogatives, without authority and without a realm continue to exist. After them, the line — ever more obscure and brought low — perpetuates itself in silence until we reach a poor carpenter who becomes the reputed father of the “woman's Seed.” Christ is born!

Thus nothing has been able to thwart God's counsels — neither Satan's efforts, nor the unfaithfulness of the kings. No doubt, these counsels have been hidden for a time until the coming of the Messiah, depicted beforehand in the person of Solomon. The throne remained empty, but empty only in appearance, until the King of righteousness and peace could sit on it. Here He is! This little Child, lowly, rejected from the time of His appearance, possesses every title to the kingdom. But see Him, hear Him! The crowds seek Him to make Him king; He hides Himself and withdraws; He forbids His disciples to speak of His kingdom. This is because before He receives it, He has another mission, another service to accomplish. He declares Himself king before Pilate and this leads to His execution, but He goes to lay hold of a kingdom which is not of this world. He abandons all His rights — not reserving a single one of them — to the hands of His enemies; He is silent, like a sheep before its shearers. This is because He must carry out a completely different task, the immense work of redemption which leads Him to the cross.

Having accomplished this work, He receives, in resurrection, the heavenly sphere of the kingdom. Like Solomon of old He is seated on His Father's throne while waiting to be seated on His own throne. This moment will come for Him, the true King of Israel and of the nations, but it has not yet arrived. He awaits only a sign from His Father to take the reins of earthly government in hand.

From the moment of His appearing as a little Child, there is no more need of a royal succession. [Note: We say “succession” because we would not forget that the “prince” or viceroy of Ezekiel is of royal seed (cf. Ezek. 46:1-18; Ezek. 48:21).] The King exists, the King lives, the King is enthroned in heaven today; soon He will be proclaimed Lord of all the earth and the offspring of David for His people Israel. But until His appearing, to maintain His line of descent, there is, as we have said, but one means: grace. This is why we have the remarkable peculiarity in Chronicles that everything, even in the worst of kings, that could be the fruit of grace, is carefully recorded. Everywhere that God can do so, He points it out. So, too, this account is not, as we find in Kings, the portrayal of responsible royalty, but the portrayal of the activity of grace in these men. The Spirit of God works even in the dreadfully hardened heart of a Manasseh in order to prolong the royal line of descent a little longer in an offspring (Josiah) who rules according to God's heart. Despite these momentary revivals, the ruin becomes increasingly accentuated. Differing in this from Kings and the prophet Jeremiah, Chronicles scarcely stoops to register Josiah's successors in a few verses before hastening to reach the end: the return from captivity, shining proof of God's grace toward this people.

In order to accomplish the work of grace which would at last bring in the triumph of the kingdom in the person of Christ, it was necessary that the dispensation of the law, without being abolished, undergo an important modification. Under the kings, the system of law continued, for it did not end until Christ; the system of grace had not yet begun, for it finds its full expression at the cross; but during the period of the kings God intervened in an altogether new way in order to manifest His ways of grace under the system of law. He did this by having prophets appear.

Not that this appearing was restricted to the system begun by the kings, for it became evident from the moment that Israel's history was characterized by ruin. Thus we see the first prophets (not mentioning Enoch, then Moses) appearing when the ruin was complete in Israel. In the book of Judges, when the entire people failed, we see the prophetess Deborah arising (Judges 4:4), and later a prophet (Judges 6:7-10). Later on, when the priesthood was in ruin Samuel was raised up as a prophet (1 Sam. 3:20). In the books of Kings and Chronicles, at last, when kingship failed, prophets appeared and multiplied beyond our ability to count them.

Note:

List of the prophets cited in the second book of Chronicles:

Nathan (2 Chr. 9:29);

Ahijah the Shilonite (2 Chr. 9:29; 2 Chr. 10:15).

Iddo the seer (2 Chr. 9:29; 2 Chr. 12:15; 2 Chr. 13:22).

Shemaiah the man of God (2 Chr. 11:2; 2 Chr. 12:5, 15).

Azariah the son of Oded (2 Chr. 15:1), and Oded (v. 8).

Hanani the seer (2 Chr. 16:7).

Micah (or Micaiah) the son of Imlah (2 Chr. 18:7).

Jehu the son of Hanani, the seer (2 Chr. 19:2; 2 Chr. 20:34).

Jahaziel the son of Zechariah (2 Chr. 20:14).

Eliezer the son of Dodavah (2 Chr. 20:37).

Elijah the prophet (2 Chr. 21:12).

Several prophets and Zechariah the son of Jehoiada (2 Chr. 24:19-20).

A man of God (2 Chr. 25:7).

A prophet (2 Chr. 25:15).

Zechariah the seer (2 Chr. 26:5).

Isaiah the son of Amoz (2 Chr. 26:22; 2 Chr. 32:32).

Oded (2 Chr. 28:9).

Micah the Morasthite (Jer. 26:18).

Some seers (or prophets) (2 Chr. 33:18-19, cf. 2 Kings 21:10).

Huldah the prophetess (2 Chr. 34:22)

Jeremiah (2 Chr. 35:2 Chr. 25; 2 Chr. 36:12, 21).

Messengers and prophets (2 Chr. 36:15-16); cf. Uriah the son of Shemaiah (Jer. 26:20).

They inaugurated a new dispensation of God, become necessary when all was ruined, when the law had shown itself powerless to rule and keep in check the corrupt nature of man; when even combined with mercy (when the tables of the law were given to Moses a second time) it had in no way improved this condition. It was then that God sent His prophets. On certain occasions they announce only impending judgment, the last effort of divine mercy to save the people, through fire as it were; on other much more numerous occasions they are sent to exhort, to restore, to console, to strengthen, to call to repentance, while at the same time bringing out the judicial consequences for those who do not give heed. Thus the prophet simultaneously has a ministry of grace and of judgment: of grace because the Lord is a God of goodness, of judgment because the people are placed under law and prophecy does not abolish the law. On the contrary, it rests on the law while at the same time loudly proclaiming that at the least little returning to God, the sinner will find mercy. It is no doubt an easing of the law: God grants the sinner all that is compatible with His holiness, but, on the other hand, He cannot deny His own character in face of man's responsibility. Prophecy does not abolish one iota of the law, but rather it accentuates, more than God had ever done up till now, the great fact that He loves mercy and forgiveness and takes account of the least indication of return towards Himself. “When the prophets come on the scene,” a brother has said, “grace begins to shine anew.” The very fact of their testimony was already grace toward a people who had violated the law. If they came looking for fruit and found nothing but sour grapes, nonetheless they announced God's promises in grace to the elect — grace as a reparation of the things which the people had spoiled. The gospel, which came afterwards, speaks of new creation, of a new life, and not of a reparation. In Isaiah 58:13-14 we see the different character of the law and of prophecy in the way in which they present the Sabbath: “If thou … ” says the prophet, “call the sabbath a delight, the holy day of Jehovah, honorable; and thou honor Him, not doing thine own ways, nor finding thine own pleasure, nor speaking idle words; then shalt thou delight thyself in Jehovah.”

Thus a special characteristic of God is expressed by the prophets. It is not the law, given at Sinai, still less is it the grace revealed in the gospel. It is rather a God who, while He shows His indignation against sin, takes no pleasure in judgment and whose true character of grace will always triumph in the end; a God who says: “Comfort ye, comfort ye My people” when they have “received … double for all [their] sins.” Under pure law judgment triumphs over iniquity; under prophecy, grace and mercy triumph when judgment has been executed; and finally under the gospel, grace is exalted over judgment because love and righteousness have kissed each other at the cross. The judgment executed on Christ has caused grace to triumph. Judgment fell on Him instead of on us — grace in its fullness, love, God Himself has been for us.

The entire role of prophecy is expressed in the passage from the prophet Micah cited above (Micah 7:18-19). It is impossible, and this is what the prophet announces here, for God to deny Himself, whether with regard to His judgments, or whether with regard to His promises of grace.

Such is the role of the prophets in Chronicles. If at first they appear singly, as in the Judges and then under the reign of Saul, of David, and of Solomon, they then multiply in the measure in which iniquity grows in the kingdom. This is what the Lord expresses in Matthew 21:34-36. After the few servants at the beginning, of whom the husbandmen beat one, killed another, and stoned a third, the householder sent other servants, more than the first, and the husbandmen treated them in the same way. At last He sent His Son.

2 Chronicles 10-12

Rehoboam

Here we reach the dividing line in Chronicles separating the reign of David and Solomon from those of their successors. As we have said above, the subject we will take up will no longer present us the counsels of God regarding the kingdom, but rather the work of grace to maintain it until the appearance of the Messiah, in whom these counsels will be realized. Thus we have here the history — ordinarily distressing, sometimes comforting — of the kings of Judah, for the kings of Israel are not mentioned except in relation to Judah and Jerusalem. This is exactly the counterpart of the account in Kings.

It is a remarkable fact — and one confirming everything we have said particularly concerning David and Solomon, types of royalty according to God's counsels — that here the Word not only omits Solomon's sins at the end of his career, but it even omits their consequences, as it did earlier in the first book of Chronicles with the chastening that came on David because of Uriah: evident proof that David and Solomon occupy a special place in these books. The accession of Jeroboam to the throne and the division of the kingdom are here presented as the consequence of Rehoboam's sin, and not that of his father; likewise, Ahijah's prophecy to Jeroboam is fulfilled, not because Solomon sinned, but because “[Rehoboam] hearkened not to the people” (2 Chr. 10:15). Moreover, we see in this same passage referred to in 1 Kings 11:31-33, that God does not intend to hide Solomon's faults, but that rather the purpose of the Holy Spirit is to omit them.

The establishment of Jeroboam the son of Nebat on the throne of Israel is also passed over in silence, which is important, for the history here is uniquely that of Judah, and not that of Israel (cf. 1 Kings 12:20). For the same reason our account omits Jeroboam's establishment of idolatry, the story of the old prophet, the illness of Abijah the son of Jeroboam, and Ahijah's prophecy on this occasion (1 Kings 12:25 — 14:20).

Rehoboam's history spans chapters 10 to 12, whereas Kings summarizes it in a few verses (1 Kings 14:21-31); but — the detail is characteristic — this latter passage presents the darkest picture of the condition of the people, whereas our chapters record the good which grace produces in the king's heart, though it is said of him (2 Chr. 12:14): “And he did evil, for he applied not his heart to seek Jehovah.” 2 Chronicles 11 tells us two important facts: Rehoboam had thought to bring the ten tribes back under the yoke of obedience, but in doing so he would have been opposing God's governmental dealings with Judah. The prophet Shemaiah turns him from a decision which would have led to his ruin and would have had the most serious consequences for the tribe of Judah, on which the eyes of the Lord were still resting, despite His judgments. Grace acts in the hearts of the people; he listens to the exhortation and does not follow through on his dangerous plan. From henceforth Rehoboam's only task was to build a system of defense against the enemies from without, enemies who were his own people and who had formerly been under his governing authority. Rehoboam surrounds the territory of Judah and Benjamin with fortresses (2 Chr. 11:5-12). His only duty was to preserve that which was left to him, but how could he do so when evil was already present within and ravaging the kingdom? However his responsibility to guard the people was in no way diminished by evil which was already irreparable.

This principle is of great importance for us. Christendom's state of irremediable ruin in no way changes our obligation to defend souls against the harmful principles which are at work. We have the sad task of raising up strongholds against a world similar to the ten tribes, which called on the name of the Lord while giving themselves over to idolatry — against a world which decks itself out with the name of Christ while abandoning itself to its lusts. We are to make Christendom understand and feel that there is a separation between true Christians and mere professors whom God ranks with His enemies. This hostility brought on the conflict between Judah and Israel, and was bound up with the idolatrous worship which Jeroboam established and imposed on the ten tribes. Public and official maintenance of the worship of God in Judah had very blessed consequences: “The priests and the Levites that were in all Israel resorted to him out of all their districts; for the Levites left their suburbs and their possessions, and came to Judah and Jerusalem … and after them, those out of all the tribes of Israel that set their heart to seek Jehovah the God of Israel came to Jerusalem, to sacrifice to Jehovah the God of their fathers” (2 Chr. 11:13-16). All those who had an undivided heart for God, even though they had been caught up for the moment in the revolt of the ten tribes, understand that their place is not in the midst of these tribes and they leave this defiled ground in order to come to Judah and settle there. This is how faithful testimony, holy separation from the world, produces fruit in believers who have hitherto been detained by their circumstances in a sphere which the Lord no longer acknowledges, and how they are moved to join their brothers who gather around the Lord. If this gathering together soon lost its character, was it not because Judah and her kings abandoned the divine ground that they might themselves sacrifice to idols? Indeed, this testimony of separation from evil lasted only a short time: “For during three years they walked in the way of David and Solomon,” and during this period “they strengthened the kingdom of Judah” (v. 17). For three years! Why didn't they continue! This was the path of blessing for Judah and her king, and is it not likewise for us? Blessing might have been complete even amidst the ultimate humiliation inflicted on Israel. It proved to be only temporary.

This momentary blessing through which the kingdom of Judah was strengthened and Israel established itself became a snare for Rehoboam. The flesh uses even God's favors as an occasion to depart from Him. “And it came to pass when the kingdom of Rehoboam was established, and when he had become strong, that he forsook the law of Jehovah, and all Israel with him” (2 Chr. 12:1). It is enough that one man, commissioned by the Lord to shepherd His people, turn aside: his example will be followed by all the rest. What a responsibility for him! Chastening soon follows: “And it came to pass in the fifth year of king Rehoboam, because they had transgressed against Jehovah, that Shishak king of Egypt came up against Jerusalem, with twelve hundred chariots and sixty thousand horsemen … and he took the fortified cities that belonged to Judah, and came to Jerusalem” (2 Chr. 12:2-4). Judah did not fall prey to their brother Israel, against whose religion they rightfully defended themselves; they fell, a much deeper downfall, into the hands of a world from which God had once redeemed them by a strong hand and stretched-forth arm — and, as of old, they were brought under subjection to the king of Egypt.

God's purpose in chastening them is proclaimed in the prophecy of Shemaiah, the prophet: “That they may know My service, and the service of the kingdoms of the countries” (v. 8). They could henceforth compare their three years of liberty and free blessing with the bondage of Egypt. As a result of the words of Shemaiah, the prophet: “Ye have forsaken Me, and therefore have I also left you in the hand of Shishak,” there was a real work of conscience in the heart of the king and his princes, for they “humbled themselves; and they said, Jehovah is righteous,” and this humbling of themselves preserved Judah from complete destruction. “And when Jehovah saw that they humbled themselves, the word of Jehovah came to Shemaiah, saying, They have humbled themselves: I will not destroy them, but I will grant them a little deliverance; and My wrath shall not be poured out upon Jerusalem by the hand of Shishak. Nevertheless they shall be his servants” (v. 7). This is grace, but, I repeat, Judah is obliged to suffer the consequences of having abandoned the word of God. All this work of repentance, the fruit of grace, is lacking — and with just cause — in 1 Kings 14. We shall see this same thing constantly repeated in the course of this book.

What shame for Rehoboam! Solomon's beautiful temple has existed but thirty years when it is stripped of its ornaments and all its treasures. Their worship has lost the splendor of its past; Shishak, we are told, took all. All! but nevertheless one thing still remains: the altar is there, God is there. For faith, amid desolation and humiliation this was much more than all the gold taken away by the king of Egypt. Is it not the same today? Christians are called upon to assess everything they are lacking as a result of the Church's unfaithfulness; and they must add, The Lord is righteous; but they may also say, God is a God of grace and has not turned aside from us. We find a very touching word for our hearts here: When Rehoboam “humbled himself, the anger of Jehovah turned away from him, that He would not destroy him altogether; and also in Judah there were good things” (v. 12). Few things, perhaps — and this is exactly what this term gives us to understand — but in the final analysis, something that God could acknowledge. Final judgment was deferred because of these few favorable little things that were pleasing to God. Let us apply ourselves, each one individually, to maintain these good things before Him. May those around us notice some measure of devotion to Christ, some measure of love for Him, some measure of fear in the presence of His holiness, some measure of activity in His service. We may be sure that He will take it into account and that as long as it continues He will not remove the lamp from its place.